Pax Romana? We were always Barbarians

- Mark Geoghegan

- Jan 27, 2022

- 3 min read

It’s wonderful how we can delude ourselves.

Over the past decade procuring pension fund ownership has become the ultimate feather-in-the-cap for insurance entrepreneurs.

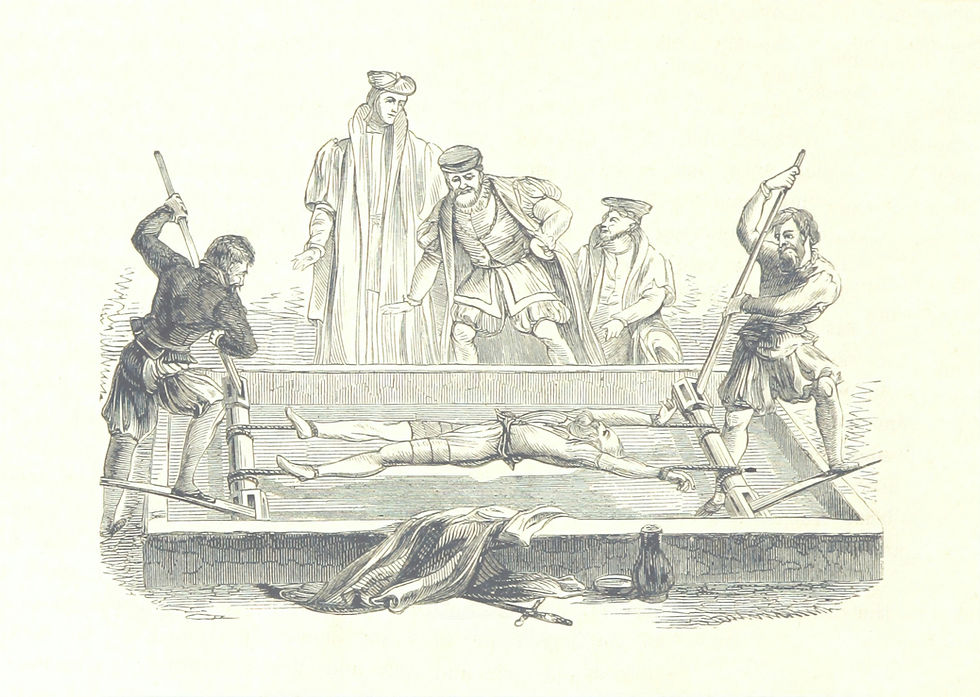

It has developed into the gold standard, the Pax Romana of privately-owned insurance capitalism.

Having a chunk of your equity owned by a pension fund was seen as the passport to becoming a citizen of a higher civilisation. Those that achieved it were better than those that didn’t.

I am sure all of us non-Canadians will admit to being a little jealous of our Canuck friends, with their dynamic and progressive fund managers buying up stakes in the best companies in the world to help fund their (presumably one day lavish?) retirements.

As more and more funds bought up chunks of the insurance space we thought it would bring a more sober, steady and supportive type of ownership in stark contrast to the unstable, rapacious Private Equity Barbarians at the gate.

And to be fair, that has been true. Until now.

The news broken by the Insurance Insider that CPPIB is looking to offload Ascot after six years has put paid to any illusions of long, peaceful and benign imperial governance by the big pension funds.

It turns out the superannuaters also go in for the 6-year flip, just like any other private equity owner worth its salt.

So much for gold-plated Roman-backed stability!

But who were we kidding?

Everyone buys assets because of just two factors. It doesn’t matter if they are private individuals buying penny stocks or mega funds taking big global firms private.

The first is because they think the asset will go up in value. Second they think they will get income.

You can have capital gains and no income and if you are really lucky you can have capital gains and income while you wait for that gain to materialise.

In private equity you generally go for the former.

You fund growth or the fixing up of the asset, and once the asset has increased in value by the amount you want, you sell. You have to sell because that is the only way of realising your paper gain.

Whether you are a pirate or a pension fund makes no difference!

When a CEO tells me their new owner ‘doesn’t ever need to sell’ that simply cannot be true in the long term.

It may be true that they have slightly less pressure to sell in the medium term, but in the end, gains must be realised or they aren’t gains.

Private equity is much better funded and organised than it used to be. For example, Howden has managed to get to the size of the old JLT without going anywhere near public equity markets (debt markets are another story).

But there will come a time when the only practical way of letting Howden investors realise their gains without periodic upheaval will be to list on a public stock exchange.

Surely that time is approaching? The inconvenience of listing and reporting requirements will eventually outweigh the burden of constantly having to find ever more and larger equity backers.

Ryan Specialty Group has just shown the way and with great success. The public markets have been starved of high-growth low-risk insurance intermediary stock for decades, so there is no reason for Howden not to become a future darling of the exchanges were it to list.

Recently I interviewed the executive team at London-headquartered MGA CFC, buzzing after a major new investment that has cemented a tenfold valuation increase in just over four years. I highly recommend a listen.

CEO David Walsh admitted that they had mulled over the idea of an IPO but carried on with private equity this round.

For the still relatively small and nimble CFC this still makes sense, but for others I’d say the clock is ticking on their private company status.

The moral of the story is that once you sell all or part of your business, no matter the new owner, that portion ceases to be yours - and that is the end of it.

So please let’s stop kidding ourselves that one person’s dollar is better than another’s. In the end all dollars are exactly the same.

Comments